Channelling Baby

Film (Trailer and Excerpts) – 1999

A perspective

Christine Parker's first feature is a mystery movie, a journey into question marks. And that isn't necessarily a bad thing: The Sixth Sense, The Ugly and The Usual Suspects were all question-mark movies, after all. With Channelling Baby, the questions can be reduced to three: "what exactly went wrong with these characters?", "whose truth can we actually trust here?, plus "why did hardly anyone go to the movies to see it?"

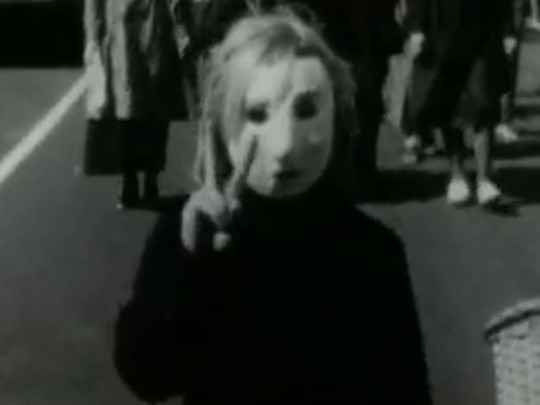

Five minutes in, the storyline has already embraced drugs, hippies, anti-war protest, google-eyed lovers to be, and the onset of a lifelong disability for one of the main characters.

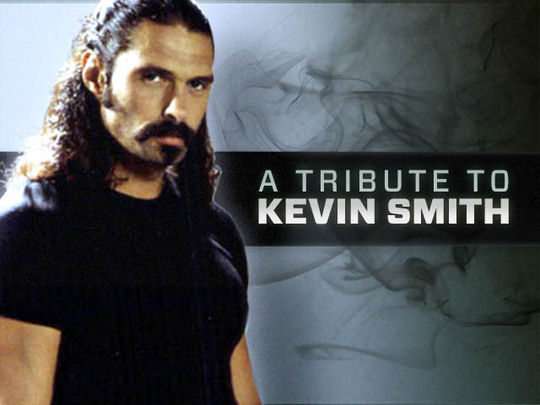

A woman meets a man. They have a baby. Bunnie (Danielle Cormack) is blind, and Geoff (Kevin Smith) fought in Vietnam. Both are freshly damaged: Bunnie by a strange incident involving staring at a solar eclipse; Geoff by the horrors of war. But something else will help bring about their break-up. Something involving their child.

Years later a mysterious young woman (Amber Sainsbury) unexpectedly enters Bunnie's life. One of the first things she mentions is the spirit of a baby: "I can feel her near you."

The young woman manages to track down Geoff, long missing in action. Finding the truth might bring the family together again. So they all meet for a seance, along with the woman's brother (Joel Tobeck), who has his own story to add.

Channelling Baby's release in 1999 rounded out a decade in which a group of women writer/directors entered the Kiwi filmmaking fray with fresh, frequently dark portraits of dysfunctional relationships: Alison MacLean with Crush, Jane Campion's The Piano, Niki Caro's adaptation of Memory and Desire.

Channelling's creator Christine Parker had already shown her rebellious spirit in a number of shorts, including domestic revenge fantasy One Man's Meat and the gloriously-titled Hinekaro Goes on a Picnic and Blows Up Another Obelisk. Though Channelling Baby would win invitations to a number of international film festivals, its box office failure seems to have counted against us witnessing more of Parker's talent.

Channelling Baby certainly offers ample evidence of talent, across many departments. Peter Dasent's eclectic soundtrack and Rewa Harre's moody lighting aid Parker, as she captures some evocative moments: the first flowerings of the couple's romance, conducted partly by wheelchair; an extended two-shot where Cormack and Smith command the screen doing nothing more than breathing; and the beautiful gloom of the seance, and Amber Sainsbury's gothic look (aided by Denise Kum's award-winning make-up.)

Yet ultimately this is Cormack's film. Often cast for her ability to bring a particular brand of emotional directness and laughter to the screen, here she shines in a new and more troubled light. Ironic considering that for most of the movie she plays blind.

The men get less chance to make their mark. Smith does some good work, but his part feels underwritten. And the film's structure relies partly on a key event where the character's actions seem unbelievable, regardless of his personal trauma levels.

Channelling Baby spins off the idea that certain moments — whether moments of trauma, or misunderstanding - can have life-changing repercussions. So can the lies which often follow. But the upside — that truth has an almost magical power to set us free — gets muffled in the film's revelation-heavy finale.

There-in may lie the problem. In the final half hour the plot revelations crash in like waves on a beach, leaving many viewers struggling to know which truth to latch onto. By now, Channelling Baby has so wrapped itself up in clever tricks that the main characters start to feel like bit players, just at the point when we should be most concerned about their plight.

Reviews for Channelling Baby crossed the gamut, sometimes within the one article. Variety reviewer David Stratton praised Cormack's "powerful" performance, but felt strongly that the climax "veers out of control". Sydney Morning Herald critic Ruth Hessey called the film "wonderful", praising its portrait of young love.

Back home, Sunday Star-Times reviewer Michael Lamb found Channelling Baby "a solid debut" for Christine Parker, of which "all involved can be proud". The Listener's Philip Matthews felt that despite some faults, Channelling Baby was ‘the kind of film we don't make enough of in New Zealand — not just weird, but deliberately weird, flamboyantly weird, a confluence of magic realism, new age spiritualism and heart-on-sleeve emotion".

So it makes some missteps. But Channelling Baby really is quite something.

- Ian Pryor is editor of NZ On Screen.