The Rainbow Collection

Beneath the Skin

You will have to forgive me if I speak personally here. But it is probably the only way I can talk about these films, some of which I either directed, wrote, or co-directed and co-wrote with my then partner in film and life, Stewart Main: About Face - Jewel’s Darl, About Face - My First Suit, Good Intentions, Desperate Remedies, A Death in the Family, One of Them! At the time — approximately from 1981 to 1996 — we were synonymous with queer filmmaking in New Zealand and closely associated with Christine Parker (Peach) and Garth Maxwell (Beyond Gravity, When Love Comes).

Stewart went on to make independently God Sreenu and Me, and 50 Ways of Saying Fabulous. I was also a co-director on Georgie Girl. As you can see, this is quite a wedge of the films and doesn’t count other films Christine Parker, Garth Maxwell and other queer short filmmakers made.

The environment in the 1980s and 1990s was both highly energised and marginalised. As homosexual men and women we knew we had no civil rights; our sexuality was illegal. It was also routinely stigmatised in the mainstream media. One thing it could not be is erotic.

At the same it was an entrancing time for queer cinema globally. The films of Pasolini, Visconti, Fassbinder and Derek Jarman had created a disruptive yet highly visual and powerful canon which contrasted with the levels of bathos of New Zealand television. (Hudson and Halls, with its portrayal of naff pre-liberation queens, was all that was allowable.) In other words, that programme was your total information about what LBGTQ life and love, potential and imagination, could be. For all its comedy, it becomes a rather dismal affair.

We set out to make disruptive films which yet had to pass through the rather narrow doors of funding acceptability. We also tried to make comments on the times. If you look at Jewel’s Darl you will see Georgina Beyer, playing Jewel, running out in front of an actual anti-gay Salvation Army march at the time of the fight for homosexual law reform. Garth Maxwell's Beyond Gravity showed two young gay men in love. Christine Parker’s Peach emphasised woman on woman eroticism — these were radical departures.

AIDS changed the landscape completely. I was aware of this when television announcers had to say the words "anal intercourse". Joke. But in a pre-AIDS era this would have never happened. It also changed the landscape as so many brothers fathers uncles and friends died. It was no longer possible to hide homosexuality away.

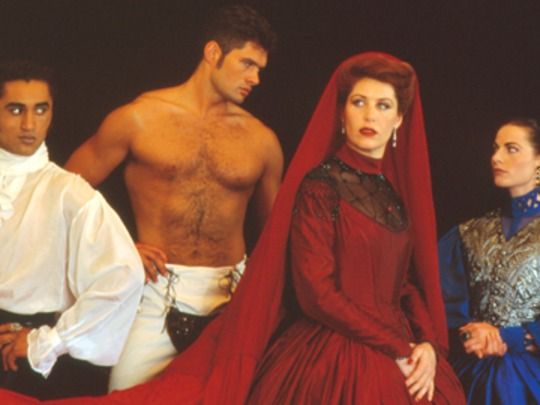

Our response was A Death in the Family, which emphasised bonds of friendship amid a frenzy of restigmatisation. Desperate Remedies, made in 1993 (when AIDS was still fatal), was full of a kind of F U flamboyance that comes from this time. Going for broke.

The outcome of changes in the law, which went alongside changes in the pandemic, was a burst of energy, of blithe joy — Hero Parade and Queer Nation both offer a kind of exuberance. Takatapui follows on from this.

In time, sympathetic insightful portraits of major New Zealand LGBTQ characters by straight directors became more common. Leanne Pooley’s documentaries The Topp Twins: Untouchable Girls and Haunting Douglas (about dancer Douglas Wright) and Annie Goldson’s Georgie Girl (Georgina Beyer) opened the world up to a broader television (and cinema) audience. This is called mainstreaming. If there was a less angular vision, less anger, the audience was broader: it is arguable whether something intrinsic had been lost.

If I can say something to end this short piece, it is a comment to do with mainstreaming: today there are so many more normalised LGBTQ characters on soaps and dramas — often courtesy of queer producers like Ryan Murphy (Glee, The New Normal). When you watch the titles in this NZ On Screen collection, however, cast your mind back — look through a glass darkly and imagine a world in which you are stigmatised, your sexuality is illegal, eroticism forbidden, and you must fight — fight to exist.

This is the invisible muscle which writhes beneath the skin of these films.

- Peter Wells won awards for his work in short films (A Death in the Family), features (Desperate Remedies), documentaries (Georgie Girl) and fiction (Dangerous Desires). He died of prostate cancer in February 2019.