Artists on Screen Collection

Visual Artist Portraits

Occasionally I hear an off-the-cuff comment that visual art doesn’t make for good film or television. Nonsense! I’m sure they once said the same about sport. Sport, like art, succeeds on-screen because of strong storytelling, commentary, camerawork and personality.

Such comment can further be knocked on the head by directing naysayers to the following stellar documentaries. Artists not only do interesting things with the material around us, they lead interesting lives. Naturally inquisitive, with an open wonder about the world, they make for inspiring on-screen company.

Anyone wanting to get recharged about the power of painting need only watch Reflections — Gretchen Albrecht. This is documentary making of the highest order from veteran filmmaker John Bates (co-directed with Karen Bates), with the experienced camera eyes of Swami Hansa and Leon Narbey, and an impressive, impressionistic piano and violin score from Tom Ludvigson.

The paint stroke holds sway here: the sweep of the camera, pace of the editing and music beautifully attuned to Albrecht’s abstraction. You sink into this film in a way that runs counter to the quick-fire editing of so much on-screen today. The commentary is incisive: generous space is given to Albrecht’s own explanation of her practice and the feelings of commentators and collectors close to her work. I love the respect given to a painter’s craft by this film, allowing us to understand the importance of process in a lifelong pursuit.

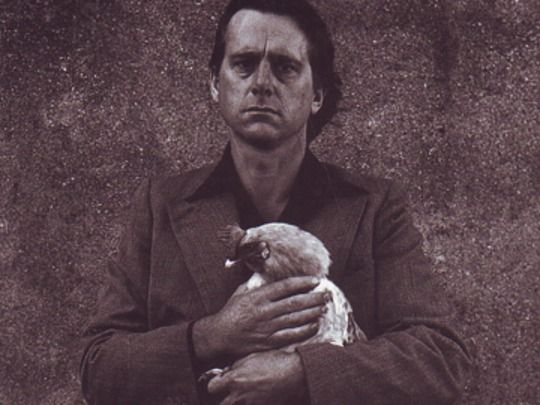

In this regard, I also highly recommend Greg Stitt‘s doco Peter Peryer: Portrait of a Photographer, again with Leon Narbey on camera. Stitt takes us out on location with the artist, to understand his thinking. The opening black and white scene, with its 360-degree camerawork of "photographer as cattle stalker" is a classic Kiwi homage to the artist’s process, and to film and photography itself.

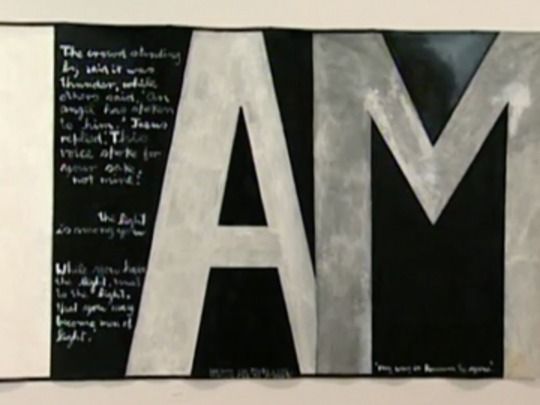

Paul Swadel’s Colin McCahon: I Am was a deserved winner of Best Documentary at the 2005 Qantas Television Awards. In the absence of a definitive McCahon biography, for a general reader/viewership this serves as a great introduction.

Swadel’s strong attention to structure echoes McCahon’s own, grounding a collage of wide-ranging biographical research, historical footage, and Leon Narbey’s brooding landscape camerawork. You get a great sense of the society McCahon was forcing his work through. As much as possible, story is related through McCahon’s own words: there’s the treat of hearing McCahon himself, alongside letters read by Sam Neill. The involvement of family, with which the doco starts, is also an important part of its success.

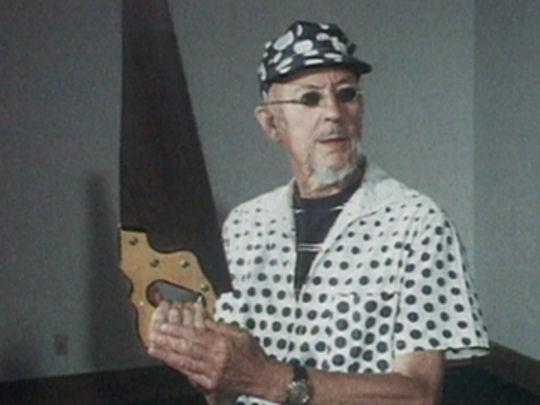

While many artist portraits step around family respectfully to maintain privacy, Pat Hanly’s whānau are centre frame in Stewart Main’s Pacific Ikon. There’s no pretence about subjective construction: the filmmaker is on camera from the get-go, with the film often kept running after the formal Q and As are over.

Recorded in Hanly’s home in the late 1990s, as Huntingdon’s disease starts to take its effect on the artist’s already exuberant unconventional behaviour, the film is marked by its matter-of-fact upfrontness in style and commentary. Importantly wife and life partner Gil and children (one born from an affair outside marriage) take equal space in telling the story. As great as so much of the painting is, the film is powerful because it is such an honest heartfelt portrait of a family; a family that could be anyone’s, enduring both the good and the bad together.

An underrated doco of an underrated artist, Michael Heath’s bio of Edith Collier, A Light Among Shadows, has a quiet, elegant spirit. Its gentleness — soothing like the slow curl of the Wanganui River that the camera rolls picturesquely over — belies the tragic story that it unfurls.

Unlike Frances Hodgkins (who was her champion) Collier followed the wishes of her family and returned to the family farm just as her European career was taking off. After a humiliating response to her modernist work by her father and local society (related by a large number of the family she was a beloved aunty to) Collier pretty much stopped painting, her confidence destroyed. Aside from the undulating Wanganui landscape, the stars of this documentary are the paintings. Work after work reveals an enormous talent.

Shirley Horrocks has done much to showcase and honour our artists on film. Flip and Two Twisters from 1995 isn’t for me her best-structured film, yet the wiry energy of art and subject make up for it plenty.

What makes Horrocks’ film particularly notable is its focus on the conversation between art and engineering, and the work of the Len Lye Foundation to realise Lye’s gargantuan ambitions, before and since his death. The film ends with some extraordinary footage by Leon Narbey of the artwork named in the title, in operation. Even on celluloid (an echo of Lye’s handmade films) it takes your breath away.

For a great piece of filmmaking by Shirley Horrocks I direct you to Questions for Mr Reynolds, a lively collaboration with John Reynolds that theatrically captures the spirit of his artistic endeavour.

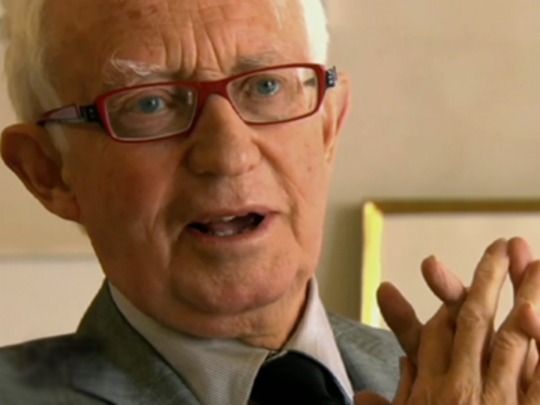

The Man in the Hat, directed by Luit Bieringa, is not only that rare thing: a portrait of an art dealer (Peter McLeavey), it’s an expression of individuality in both subject and approach.

A passionate yet stately performance of his occupation by McLeavey powers the filmmaking. McLeavey’s words often have a meditative poetic form that echoes the literary, ecclesiastical and working man’s commonsense of his Irish Catholic upbringing. "These are my vestments", he tells us as we observe him in his bedroom adjusting his suit. "These are my overalls. I’m a good worker. They distance me from my clients as well. They separate me from the world."

This gentle theatricality — the sense that serving artists requires you to sit apart — imbues the film. It is structured around McLeavey’s walk from home to the gallery, and also amidst, surreally, the polystyrene rubble of a dismantled Peter Robinson installation.

It’s also about the business of art dealing ("This bird has flown" he says, recounting one almost sale), and the relationship between dealer and artist. An interesting exchange of letters with Colin McCahon also threads throughout. Plus there’s a loving portrait of Wellington’s Cuba Street. The cinematographer is — you guessed it — the remarkable Leon Narbey.

Of New Zealand filmmakers, Tony Williams has had one of the most interesting careers. That’s plainly evident from a favourite curio in this online library, Takis Unlimited, a 1969 documentary Williams edited about Greek kinetic and sound artist Takis. Williams' editing reflects the artist’s playfulness with flashing, magnetic and oscillating mechanical forms, and the buzzy social scene around him as art broke free of the pedestal. "Art should be played with and then thrown away", states Takis at one point. Yet ironically the second half of the documentary focuses on the reproduction of multiples of Takis’ work as babyboomer consumer décor.

For a time capsule of New Zealand and a bit of a giggle, also check out Williams’ first film, The Sound of Seeing, from 1963. In a collage of experiences, a painter and friend wander through the city, alive and seemingly stoned to the sounds of the city and surrounding environment, and translate them into abstract marks. The painting produced looks decidedly average cod modernism, but it’s an adventurous piece of filmmaking and a fascinating cultural snapshot of Wellington on the eve of huge cultural shifts. It’s also so close to how we’d comically pastiche this period as to be laugh out loud funny. The serious, bearded artist perpetually lighting his pipe while a jazz combo jives on. How far we’ve come.

Finally, arguably the finest documentary of an artist I’ve seen is also one of the oldest. Yet — with thanks to NZ On Screen — it’s the one I’ve seen the most recently: Ralph Hotere. Ian Wedde and the director Sam Pillsbury express beautifully in essays here on-site what’s so special about Hotere from 1974: the artist's perspective expressed through watching him work, while hearing the chatter around him.

The documentary’s ultimate subject — with a precious amount of interviews with leading commentators and writers from the time — is how we talk about art. It’s a very smart piece of filmmaking, best exemplified by the closing segment of Hotere playing chess while Waikato Pākehā celebrate ‘Founders Day’ and officially launch Hotere’s impressive mural in Hamilton’s Founders Theatre without him.

Mark Amery has been writing for the visual arts in New Zealand for over 20 years. He co-hosts Radio New Zealand arts show Culture 101. Amery was visual arts critic at The Post, contributes regularly to eyecontactsite.com, and co-founded public art project Letting Space.