Strawberries with the Führer

Film (Full Length) – 2011

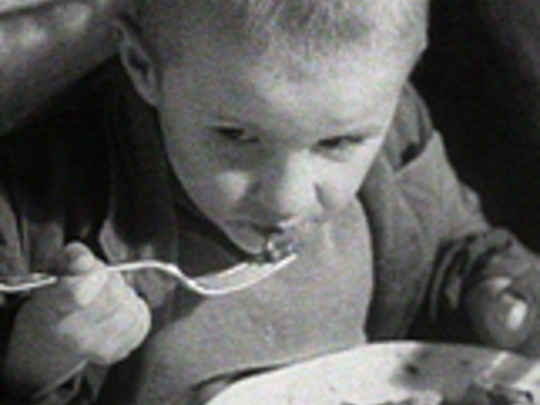

In the early days I remember tuning into a radio broadcast which came on at seven o'clock just after we had tea, and they always started with great marching music which was wonderful to listen to, and then you had reports of the German army advancing victoriously here and there and everywhere. There was never any report of so and so many people were killed, and never reports of heavy losses or never reports of any civilians being hurt. It was just advance, advance, advance, yeah. And you felt good about it, you felt proud about it, you never thought of what it entailed as a 10-year-old, 11-year-old, you don't.

– Helga Tiscenko on listening to state media broadcasts about WWII while living in Germany

I said to my dad, 'What do you want us to do if the Russians get here first?'. And he looked at me, grabbed me and said, 'They will not get here. You are talking treason'. Now imagine a father saying this to his 15-year-old daughter: 'You are talking treason. Do not even think that. They will not get there...'

– Helga Tiscenko on her family's precarious position as Allied forces arrived in Germany during WWII

Certainly when I was younger I had an enormous sense through my teens and through my 20s and 30s, and even to an extent now, but it sort of lessens as you get older and you understand things on a deeper level...but I certainly did have a terrible sense of . . . there was shame there, there was guilt there. For instance whenever I discovered that one of my friends, especially in the Wellington years, if I discovered that a friend had Jewish heritage, my hand would go out and I'd want to touch them and say, 'I'm just so so sorry'.

– Katerina Tiscenko on living with the painful knowledge of her family's involvement in mass suffering

She wanted people to understand the danger of regimes. She knew history could repeat so wanted people to be aware of regimes. If groups are marginalised it is easy to get carried to the next step where people can be attacked. She taught all of her children, and we’ve passed it on to our children that when a regime starts categorising and marginalising a group, it is the first step to something like the Holocaust. Mum taught us to be very careful and stand up when people try to marginalise others for beliefs, religion, or ethnicity.

– Katerina Tiscenko on the purpose behind her mother's memoir Strawberries with the Führer, Stuff, 10 January 2023

He sat down next to me and then we ate strawberries with vanilla ice cream together. I took care not to spill on my blue dress, and my child's heart beat only for him. If he had asked me at that moment if I would die for him here and now, I would undoubtedly have said yes...

– Helga Tiscenko recalls meeting Hitler in her memoir Strawberries with the Führer' Stuff, 10 January 2023

She was more than just the little girl who had strawberries with the Führer — that was only a small part of her life. She had a very rich life in New Zealand and was a very proud Kiwi. Mum and Dad were so grateful that they could come to New Zealand.

– Katerina Tiscenko remembers her mother, teacher and author Helga Tiscenko, and engineer father Nicholaj Tiscenko, Stuff, 10 January 2023