The Men on the Hill: Keith Holyoake (First Episode)

Television (Full Length Episode) – 1965

Live on the news: Holyoake meets protestors. Viewers don't see it.

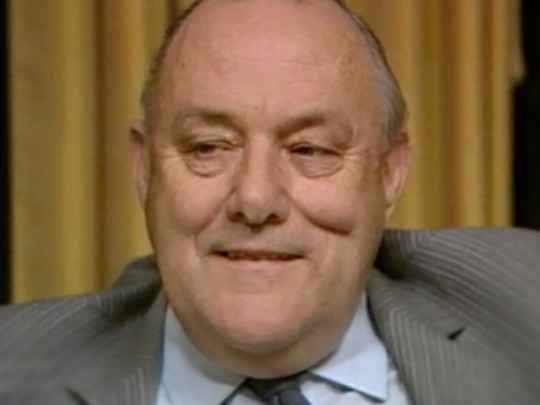

In the mid 60s Prime Minister Keith Holyoake had a historic but unintentionally comic encounter with some Vietnam War protestors, live on the primetime news. Former NZBC-TV stage manager (and later producer) Derek Morton was there.

After a first naive flush of enthusiasm when New Zealand television began in the 1960s, local production had tended toward pallid and parochial programmes. The bosses were civil service ex-radio types: a dull, insipid lot, but the executive offices were enlivened by the arrival of Allan Martin and Alan Morris, Kiwis who had worked in TV in Britain, and returned to give things a shake.

Allan Martin set up Compass, a poor colonial cousin descended from British current affairs shows like Panorama and World in Action. Launched with enthusiasm in 1964 over Head Office reluctance and timidity, it starred Alan Morris as front man.

In mid 1965 Prime Minister Keith Holyoake was due to return after a trip which included a Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ meeting in London (where it was decided to send a Commonwealth Peace Mission to Vietnam) and an ANZUS Council Meeting in Washington.

Before departing, 'Kiwi Keith' had announced the Government’s decision to send an army combat unit to "struggle against communist aggression" in Vietnam, and stated he had some practical suggestions to end the Vietnam conflict, details that would only be revealed after he returned. As a result, the media awaited him with more than usual interest.

Allan Martin decided that the outside broadcast van - usually left sitting idle in a garage between sports events — should be set up to capture Holyoake’s arrival at the airport, and an interview. The material would be played back from videotape shortly afterwards, into the primetime evening news. In the event, the plane was slightly delayed, touching down while the news bulletin was on air. Even more immediacy! Martin decided to go live.

The plane landed. Holyoake and his retinue came into the VIP lounge near the tarmac. After a respectful pause I approached the great man to confirm he was ready to emerge into the terminal concourse. On thousands of TV screens the telephone on the studio newsreader’s desk, never previously used, rang, and "we now take you live to Wellington airport...". For the first time in New Zealand we were live to air on the primetime news from outside the studio.

After a short introduction by reporter Nigel Bingham, the plan was for the camera to follow Holyoake as he walked across the terminal and into a room for his interview. Peter Morritt, operating the camera high up on a camera crane, panned away from Bingham and zoomed into the door leading from the VIP lounge, awaiting Holyoake’s appearance. But nothing happened. Bingham, stuck live on air with no more script, desperately adlibbed, while viewers were treated to a shot of an empty doorway for two and a half minutes - an eternity in television. Finally there was a flash of action as I dashed through, on the way to talk to Allan Martin on the communications link.

"Allan, just after Holyoake said he was ready to come out, a bunch of Vietnam war demonstrators arrived out here, and now he refuses to move. I just can’t persuade him."(What Holyoake had actually told me was 'I’m not going to be seen with those freaks!').

Martin briefly pondered a change to the rehearsed plan. "Well tell him we won’t show him with the demonstrators."

While I communicated this proposal to Holyoake, Martin quickly arranged through headphones with Peter Morritt to frame a shot that Holyoake could walk out of before the demonstrators came into view.

Holyoake finally emerged, to the relief of the audience — and greater relief of Bingham, still struggling to keep words coming out of his mouth. Morritt held Holyoake expertly in shot as he crossed the concourse, ready to let him walk out of shot as planned, before the demonstrators were seen. Then Morritt suddenly found himself having to pan in another direction, as Holyoake, hit with an inspiration, decided to walk around the other side of the camera crane, away from the demonstrators. But Holyoake’s experience was in politics, not television production. The area behind the camera crane on that side was not lit, and in any case Morritt was not set up to pan in that direction, and quickly found himself left without a shot.

Conscious his camera was carrying the main news bulletin live on air, he searched desperately for something to fill the frame. There was nothing in the lit area but the group of demonstrators, so Peter quickly framed them up. With a great big camera pointing right at them, red cue light glowing, the demonstrators lost no time in waving their placards at it and shouting.

Holyoake, by this time entangled in a mass of cables and equipment in the murk behind the camera crane, was confronted with the overalled figure of Wag Lee, a veteran cockney technician. "Oy er...sir. Ya can’t come round ‘ere," said Wag. By now Holyoake himself must have realised it would be nearly impossible to thread his way through the clutter of equipment, and decided to return to the lit side of the crane, and brave the demonstrators after all.

While this was going on, Martin was desperately calling through the headphones to Morritt. "We have to get off them." "But I’ve got no other shot." "Shit Peter, give me anything, anything but them."

Behind the demonstrators was a low partition wall enclosing the airport cafeteria, where a few people sat at distant tables having tea and sandwiches. Morritt pointed his camera at this curious, mysterious and irrelevant scene. Bingham continued to waffle on manfully, now several minutes into unscripted blather.

Holyoake soon reached the demonstrators, stopping to make a great show of reading their placards and chatting amiably. Not that viewers, bemused by two or three minutes of a shot of people drinking tea, and the desperate voice of Bingham offering up platitudes, got to learn anything at all about it.

Finally, Holyoake moved on, to the room where David Inglis awaited him for a live interview. A retinue of cabinet ministers followed, who had come to the airport to welcome him. Within seconds the crush of people in the small narrow room had obscured the lenses of both cameras; there was nothing for it but to clear the extra bodies out, fast. There was considerable resistance, and Bingham’s desperate attempt to maintain his commentary was drowned out by outraged shouts like "look here, I'm the Minister of Justice", as assistant stage manager Bob Blair and I shouldered various worthies out the door.

After less than a minute the room had cleared enough that the interminable tea-drinking scene could be replaced by a shot of the interview area. Thankful we were at last under control, I turned back to our interview setup to see (along with the primetime news audience) Holyoake pull out a cigarette, light it, and boom in his unique voice "Well, when do you boys want to start shooting?" It was his introduction to live television.

Oddly, the videotape recorded from the live transmission of this flamboyant disaster mysteriously disappeared from the studio overnight. We never saw it again.