Auckland

Finding Auckland

When I was a kid growing up in England, Auckland was painted in myth. My dad — Eugene, born in Fiji, raised in Auckland — told us stories that made it a scary, romantic place. Octopuses attached themselves to my uncle’s legs as he walked through the sea; men would sit around giant whisky bottles for four days straight; the sand at some beaches was so black you’d burn your feet if you didn’t run. Only occasionally, when Dad’s mate Allen Guilford — the late, great Kiwi cinematographer — would visit, we’d get a sense that Auckland was a real place, a place of mortals. And even rarer, we’d get a glimpse of Auckland on TV, most memorably during the first World Cup, in 1987. I wanted Auckland to look like Michael Jones. Children of Fire Mountain and Worzel Gummidge Down Under made it to our screens over in England, too (I can still remember the theme tune to the former).

We moved back to Auckland on the cusp of the 90s (the day TV3 launched, actually: "TV3 come home to the feeling, TV3 come home to the beeeessst …") It was raining hard as we drove back from the airport, to Mt Roskill, past the power station on White Swan Road. And it sure didn’t feel like a land of coconuts and hula skirts, and it wasn't a City of Sunlight as the National Film Unit had promoted it in 1946. Our own idea of the Pacific had become almost as warped as that of Robert Flaherty’s, in original 'documentary' Moana (1926).

At the time, especially for a teenage boy with a Pacific background, Auckland was all about the gangs: TCGs (Tongan Crypt Gang) and SOS (Sons of Samoa). Names like Principle T were on walls all around the streets, but the writer never seen. Everybody knew the story of the guy who got killed in a machete attack in Otara.

My cousins were right in the middle of this world, not really loyal to any crew but themselves. They were feared. There were even 'I HATE THE FRASERS' T-shirts at one stage. One of my cousins got me over to his place in Sandringham on one of those early days to do weights. I couldn’t lift my arms for a week. Within a few months, and after some brutal scraps, the cops were following me home from the train station.

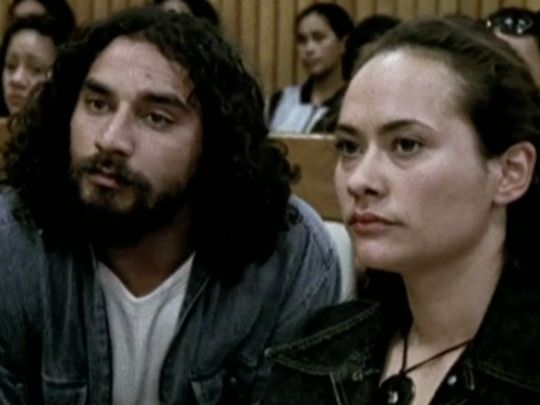

It was tempting, then, to imagine this as the real Auckland, the real Pacific: far removed from the place of abundance Flaherty depicted, and a long way from the tranquility implied in Magellan’s name for our ocean. It was an Auckland reflected more in the oily puddle of a Once Were Warriors junkyard than in the sea beneath an End of the Golden Weather pohutukawa tree: a place of blood and broken jaws and kicking a guy when he’s down, dust spraying, adrenalin pumping.

It’s tempting, now, to think of Auckland in similarly isolating terms. It’s tempting, when we try to imagine Auckland, with its seemingly disparate suburbs, its painful transport and network infrastructure, to think of it as a collection of villages. It’s tempting to think that it's not really a city at all, just a collection of tribes (SUV-driving Remuerans, latte-sipping Ponsonbyites, the KFC-munching Mangerese, suburban fringe dwellers) defined by and confined to their separate spaces.

But just as the late, great writer Epeli Hau’ofa encouraged us to think of the Pacific as a Sea of Islands, inferring that the meaning of our vast, watery continent reveals itself in the ocean, not in discrete blocks of land, so it is with Auckland. We won’t find the real Auckland in Epsom. We won’t find it in Birkenhead or Mt Roskill, or Otahuhu Shopping Centre or Britomart. The real Auckland is in its diversity.

It’s in its imagination and its stories. It’s in the spaces in-between: it’s somewhere between Outrageous Fortune and Gloss. Somewhere between Praise Be and Hero Parade. Somewhere between the ground-breaking series of Pasifika short films, Tala Pasifika, and Walkshort...and it spans Manurewa, Queen City Rocker, No. 2 and bro’ Town (where I finally did get to see Auckland and Michael Jones animated together on-screen).

Around the time that Sione’s Wedding and No. 2 were released, Sam Neill spoke about how his thesis of New Zealand cinema as a Cinema of Unease now needed to be reviewed; that New Zealand was developing a cinema at ease. It is in here, in the diversity highlighted by this collection, and in the aim that we as Aucklanders, as people of Oceania, as people of this Sea of Islands, will continue to tell our stories, more varied and more nuanced; that we will further develop our ease with this beautiful, dark, scary, romantic place.

- Toa Fraser turned his play No.2 into an award-winning 2006 feature, shot largely in the Auckland suburb of Mt Roskill. Since then he has directed te reo action, documentary and American superheroes.