Black Gold

Black is not a colour

Black is not a colour. Nor is it simply an absence of light. Black is an absolute, which, for more than a century, has been the thread, running through our sporting success.

Black both describes and differentiates us.

New Zealand-born writer and comedian John Clarke said that what separates us most from those born elsewhere is the final letter of the alphabet. He believed that a New Zealander's eye will be naturally drawn towards any word with a 'z' in it. We are, he argues, imprisoned for life by our backstory. In sport, black has a similar capacity. In a stadium filled with colour, we will be forever drawn towards the black.

NZ On Screen has called this collection Black Gold — and it is the colour black that dominates the most memorable screen images of Kiwis atop Olympic, Commonwealth and Empire Games podiums. Even — perhaps more so — in the black and white archive footage.

No colour makes a statement quite like it and, for more than a century, in some of sport's most storied places, the black uniform has spoken exclusively for us.

Like our nearest neighbours, our national uniform has no relationship with our national flag. From a distance, our flags could be the same; not so, our gear.

The 1888-89 New Zealand Natives Team were the first to combine a black uniform with a silver fern, but in an Olympics context, we have been identified in black since our first Olympic Games as an individual nation, in Antwerp in 1920.

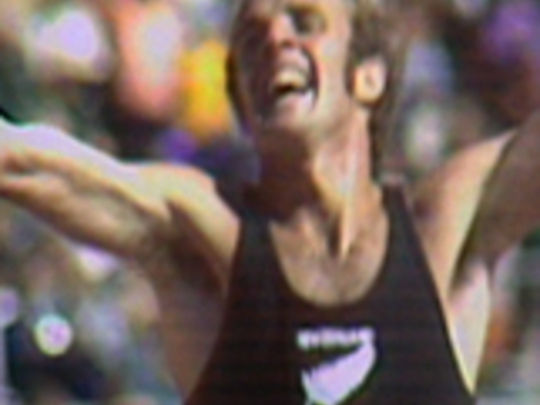

There have been brief flirtations with highlight colours of grey or teal or white, but essentially when you saw a black singlet you knew he or she was one of ours, and therefore someone to support and perhaps even to celebrate.

Several years ago, I was able to convince Peter Snell to return to Cooks Gardens for a photo shoot. It was part of a Sky Sport - The Magazine photographic series called Shrines; the idea being to reacquaint New Zealand sporting greats with a significant place in their history.

Snell was in New Zealand from his Texas home for a few weeks and though on a tight schedule, generously gave a few hours to myself and a photographer for what we hoped would be an enjoyable reunion.

I had come prepared. Earlier that week I had made a call to Athletics New Zealand, asking to borrow a team uniform. The material and style had evolved significantly over the years, but two things had not changed. Each was still adorned with a beautiful silver fern on the front, and they only came in black. There was complete indifference to my request right up until I was asked what I wanted it for.

"I'm giving it to Peter Snell to wear at Cooks Gardens."

Instantly. "Where shall we send it?"

It had been nearly 45 years since Peter had last run for New Zealand, but his name still had pulling power. I had seen the newsreels of him, and spoken to many who knew him, but nothing prepared me for the man. Because when people tell you someone has presence, they mean someone like Peter Snell.

When I handed him the uniform he was, at first, reluctant. "I'm not as young as I once was", he explained. "I don't want to embarrass myself." The thought of a Peter Snell of any vintage embarrassing the black singlet was an impossibility of which I was eventually able to convince him. He was close to 70 by then, and though parts of his once indestructible body were starting to fail him, there was a lightness in his stride that was impossible to pretend.

Cooks Gardens had changed, too. The grass oval on which he ran the mile in a world record 3 minutes, 54.4 seconds in January 1962 had been replaced by a more functional all-purpose synthetic track. But you could tell he loved being back. Not even the years could completely separate the man from his moment, and the photograph we came away with remains one of my favourites.

I had prepared for the trip by revisiting some of the archival footage of his greatest successes. There is only blurry archive footage of Snell racing at Cooks Gardens that night (seen 16 minutes and 40 seconds into this clip). Much crisper footage exists from Lancaster Park in Christchurch the following week, when he broke world records in both the 800 metres and 880 yards.

Snell was always a powerful runner, but in Lynton Diggle's Peter Snell - Athlete it's impossible to escape the grace of his performance: bounding through Waitākere bush and vaulting farm fences. Arthur Lydiard may have endowed him with the ideal training regime, but Snell was the perfect collision of physique, determination and ability.

The International Olympic Committee is famously protective of its television rights these days, so there may never be a greater record of our Olympics achievement than John O'Shea's 1968 documentary The Glow of Gold. It is revealing in its honesty and its reflection of a simpler time. Those chained to the belief that the story of sporting success is written only by the winners will be charmed by Marise Chamberlain, who fails beautifully to hide her excitement at winning a bronze medal in the Tokyo women's 800 metres.

Or its decision to follow West Coast marathon runner Dave McKenzie as he prepared for the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. McKenzie had won the famed Boston Marathon just the year before so was an obvious subject, but on the day he was 37th, while another New Zealander, Mike Ryan, claimed bronze. The other Mexico-bound athlete profiled in the doco, rower Warren Cole, proved a safer bet: winning gold in the coxed four.

The essential uncertainty (and allure) of sport is the focus of two documentaries: Pieces of Eight follows the world champ Kiwi rowing eight's quest for an Olympic title at the LA Olympics, and Games 74, dares to interview the defeated in its chroncile of the Christchurch Commonwealth Games. It features the famous 1,500 metres race where John Walker broke the world record but finished second to his great rival, Tanzanian Filbert Bayi.

Though gold didn't end up framed by black singlets in either race, both titles exalt the spirit of competition. This is the focus of Lee Tamahori's mini-epic Join Together. Made to promote the 1990 Commonwealth Games in Auckland, it's a casting call for some of our greatest acting talent, from a young Joel Tobeck to Bruno Lawrence in his prime, who winningly pitch that it is noble and sweet to compete for one's country.

Chas Toogood's Triumph of the Human Spirit, a documentary of the 1996 Atlanta Paralympics, is also a triumph of storytelling, which somehow manages to squeeze Paul Holmes, Superman and the burning of Atlanta into the first few minutes. Like many titles in the collection, it contains gold of another kind.

All the titles, in their way, remind us that while not every New Zealander follows or even appreciates sport, it is impossible to avoid its influence.

Black is not a colour.

And there is nothing basic about it.

- Broadcaster Eric Young hosted the London 2012 Olympic coverage for Prime TV. The ex-Auckland Star sportswriter has reported for ESPN in Singapore and presented the news for Prime TV and Sky. He edited Sky Sport - The Magazine, and was named 2008's Sir Terry McLean Sports Journalist of the Year.