The Governor 5 - The Lame Seagull (Episode Five)

Television (Full Length Episode) – 1977

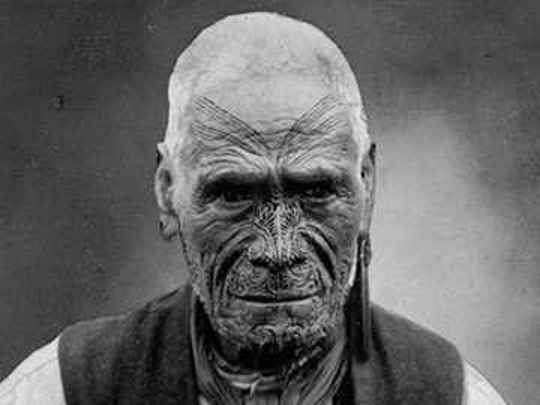

Friend, I shall fight you...forever and ever.

– Chief Rewi Maniapoto (Wi Kuki Kaa) makes a legendary statement of defiance, at Ōrākau

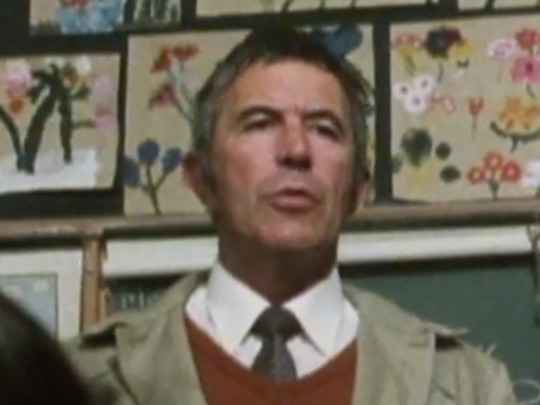

I come 12,000 miles to put down a rebellion by a group of savages. They fight on, hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned. And then one of these 'savages' writes to me, complaining that so-called civilised Europeans are not observing the basic rules of humanity. And I start to wonder — who is the savage?

– General Duncan Cameron (Martyn Sanderson) berates his men for committing rape

The decision to use the Māori language was courageous, I think, part of the integrity with which this whole thing was approached. In the past it's been lip service, tokenism...

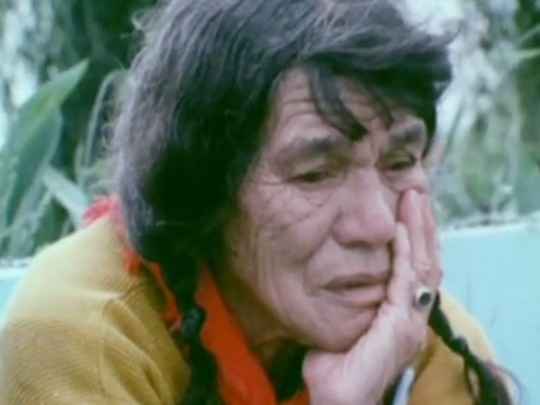

– Actor Don Selwyn on the revolutionary decision to use te reo Māori in The Governor, The Listener, 1 October 1977, page 40

..we're getting a Māori point of view, which hasn't been written, but which has been handed down from generation to generation by our tipuna, and by our living elders...

– Actor Don Selwyn, in documentary The Making of The Governor (clip two)

Last week's story, The Lame Seagull, showed much more certainty of purpose [than episode one], but was in itself episodic ... I have, like the majority of my fellow-viewers, nothing but the highest praise for each part of the production itself ... Magnificent camerawork, lighting, sound and special effects ... The script, too, is of a high standard, delving — unlike The Mackenzie Affair — beneath the surface of events in search of their real significance.

– NZ Herald reviewer Pamela Cunningham, 5 November 1977

Māori children have been excited by the series because for the first time it has shown the Māoris as the goodies, says Dr Walker.

– Auckland Star interview with Auckland District Māori Council chairman Ranginui Walker, 5 November 1977

Previously people tended to deny the wars ever took place. About 15 years ago when I raised some of the issues they fought for, I was told I had a chip on my shoulder and to forget it.

– Auckland District Māori Council chairman Ranginui Walker, The Auckland Star, 5 November 1977

[Producer Tony] Isaac and his team approached the Māori side of The Governor with care, and with respect, aware of the European slant of our history books. The result Isaac says is Māori viewers might get more from the series than Pākehās.

– Writer Hugh Nevill, The Listener, 1 October 1977, page 39

[Stunt man Jerry] Popov had to come out of a burning whare, alight, as a burning woman. The first time, he came out in Pinex, looking like a sandwich-board man, with a tiny flame flickering around him. The next time he tried an asbestos fire suit, but that didn't look authentic...On the third take he spilt the petrol and the whole village went up. All the crew fled, except the faithful cameraman ... The fourth time, Popov caught alight nicely, but came out flaming before the whare caught fire. They got it right in the end.

– Writer Hugh Nevill, The Listener, 1 October 1977, page 39

Up to now we have been living under the myth of harmonious relations between Māori and Pākehā. This is a fine ideal but it shouldn't blur the reality of history. People may now understand why the Bastion Point protestors are camped on Crown land and why groups like Ngā Tamatoa exist.

– Auckland District Māori Council chairman Ranginui Walker on the importance of The Governor, The Auckland Star, 5 November 1977

It was the most highly-rated drama series, overseas or local, ever to be screened in this country.

– Television executive Des Monaghan on The Governor, The Listener, 28 October 1978

Auckland's Mayor, Sir Dove-Myer Robinson, warns of reopening old wounds and is worried about some of the comments he has heard from young Maoris.

– Auckland Star writer, 'Governor rekindles fighting spirit', 5 November 1977

Pākehās say the portrayal of the wars has been one sided and anti-Pākehā. Māoris think it is accurate and showed who really was exploited.

– Second paragraph of Auckland Star story on reaction to The Governor, 5 November 2011

General Sir Duncan, friend. At the taking of Waipā, a young Māori girl, Huia Kiini, was attacked by your soldiers. Her eye was damaged and they forcibly committed adultery with her. As you are a Christian man, I know you will be sad that the law of God has been broken. Thank you for the keg of tobacco.

– A letter from Wiremu Tāmihana is read out by Major Edward Gordon (Peter Hayden) in front of the troops

I'm a soldier. I fight battles — I don't cause them.

– General Duncan Cameron (Martyn Sanderson) after he unexpectedly encounters Wiremu Tāmihana (Don Selwyn)

Perhaps no Pākehā will ever understand.

– Wiremu Tāmihana (Don Selwyn) tries to persuade General Duncan Cameron (Martyn Sanderson) that the war is actually so Pākehā can get land

Have a strong sentry posted at the stream. Keep up the bombardment until dawn. If they can’t sleep and they can’t drink, we may still force a surrender.

– General Duncan Cameron (Martyn Sanderson) to Colonel Carey (Terence Cooper)

Ki te mate ngā tāne, me mate anō ngā wāhine me ngā tamariki.

– One of the women present at the battle of Ōrākau

If the men die so too shall the women and children.

– One of the women at the battle of Ōrākau

I remember once, coming home from a shoot up the Moonshine. We crossed the Hutt River in full uniform and 'stormed' Avalon.

– Actor Norman Fletcher (who played Corporal Johnson) recalls making The Governor

It was total chaos, the reality of going out there and shooting. We were trying to do basic things, like re-location at night. There was no electricity there, no nothing. You had to pull generators through the mud and there was no communication, no cell phones.

– Peter Muxlow recalls the challenges of directing this battle-heavy episode, in Trisha Dunleavy's book Ourselves in Primetime - A History of New Zealand Television Drama, page 104

If the men die so too will the women and children.

– One of the women present at the battle of Ōrākau

In 1860 he [Duncan] received command of the troops in Scotland, an appointment prized among Scots officers. His next posting, in 1861, was even more highly valued: chief command of an army at war, in New Zealand. At this watershed in his career Cameron was considered one of the most accomplished officers in the British Army. His reputation could hardly have been equalled among junior generals. Five years in New Zealand were to change all that.

– Historian James Belich in his profile of Duncan Alexander Cameron, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography/Te Ara website (1990, updated in 2010)

Governor Thomas Gore Browne was planning an invasion of Waikato to crush the Māori King movement and, at a meeting of the New Zealand Executive Council, Cameron enthusiastically supported this course ... Then, in mid 1861, Browne was sacked and replaced by Governor George Grey, and, to Cameron's bitter disappointment, the invasion was called off. Balked of the war he had come out to fight, Cameron apparently sent in his resignation in early 1862, but the War Office declined to accept it. Grey consoled Cameron by hinting that the invasion had merely been postponed, and by authorising active preparations for it. But, as Grey seemed to vacillate, his relationship with Cameron wavered between efficient co-operation and mutual recrimination, as it was always to do.

– Historian James Belich in his profile of Duncan Alexander Cameron, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography/Te Ara website (1990, updated in 2010)

He [Duncan Cameron] was deprived of due credit, first by Māori fighters, who, with their revolutionary modern pā, prevented him from achieving outright victory, and next by Pākehā writers, who attributed his lack of success in battle to incompetence. Yet his influence was profound: it was Duncan Cameron at Pāterangi, not William Hobson at Waitangi, who sounded the death-knell of Māori independence.

– Historian James Belich in his profile of Duncan Alexander Cameron, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography/Te Ara website (1990, updated in 2010)