The Florian Habicht Collection

Talking to Strangers

When I think of the documentaries made by Florian Habicht, I think of the word joy. In fact it's entirely possible that Habicht spends more time smiling than anyone around him (see this interview, if you want proof). His films are rife with joy — a joy in taking risks, in leaping from reality into flights of the imagination. But most of all they share a joy in likeable people, busy being themselves on screen. As Habicht has said, he loves "to celebrate people's idiosyncrasies".

As the child of a German photographer and an Austrian nanny — who found himself attending high school in Northland — Habicht's teenage interest in photography helped him to conquer his shyness, and connect with others. These days, he hardly seems the shy type. Love Story (2011) reveals Habicht in action, enlisting the help of strangers to figure out where the film will go next. Some of these encounters were likely set up in advance, but there's no denying his ability to connect with people, and persuade them to go before the camera. Habicht combines an artist's sensibility, with a journalist's instinct for when to ask the question — and when to shut up, so the talent can shine.

And shine they do. Habicht's third film Kaikohe Demolition (viewable here in full) is built around a bunch of small town locals in the Far North, who live for the days they can jump in a car, and smash into each other in the local demolition derby. Petrolheads aside, I suspect most viewers would rather be cutting their fingernails than risking this kind of whiplash. Yet the film's sense of people who so clearly know what fun is, and how to find it, is truly infectious.

Costa Botes has written about the engaging bouncer who loves bashing up cars, and also runs an anger management group because 'I don't believe that people deserve to be beaten up'. Fellow local Uncle Bimm provides a shot of joy, every time he turns up. Great music (by Marc Chesterman) turns the demolition scenes into some kind of ballet.

Habicht returned to Northland for Land of the Long White Cloud (also viewable in full). Again the film's best feature is its cast of real life Kiwis, this time participants in a fishing contest on Ninety Mile Beach. The moody images of anglers against sea and sand are a definite step up from Kaikohe Demolition.

In between his two Northland documentaries, Habicht made a second venture into biography (following his little seen 2000 debut Liebestraume - The Absurd Dreams of Killer Ray, inspired by cult jazz entertainer Killer Ray).

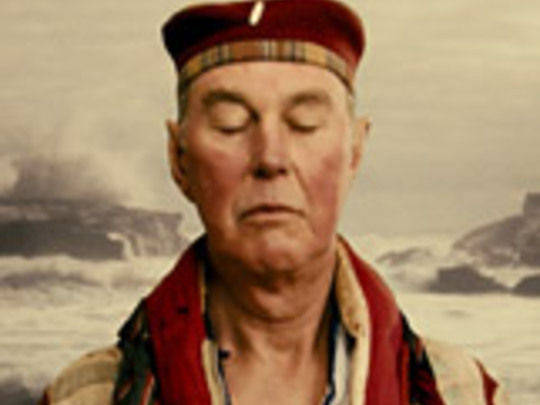

Rubbings from a Live Man is described on the poster as 'a documentary performed by Warwick Broadhead'. Sometimes confronting, often beautiful, the film mixes up close interviews, with an awareness that artists often speak best via their art — a tricky scenario in this case, since the veteran stage performer had prevously refused to let his work be filmed. Habicht's generous approach to collaboration is clear; the closing credits say Rubbings was 'conceived and realised' by a team of four (including Broadhead, and frequent Habicht collaborator Christopher Pryor).

The film contains remarkable scenes where Broadhead has the courage to face up to his own weaknesses, by pretending to be another person entirely. As Habicht has argued, the film uses performance to get closer to the truth. In one sequence, an emotional Broadhead calls a halt to filming. He appeals to Habicht's humanity, since "I can't tell the story anymore". Many filmmakers would have quietly filed this moment away.

In 2014 Habicht found a new angle on the music documentary: his movie about Brit pop group Pulp circles beyond singer Jarvis Cocker and company, to locals in Sheffield — the city where Pulp began, and had their final concerts.

I'll be at the front of the line for the NZ International Film Festival debut of Habicht's documentary Spookers — which introduces viewers to the team behind a live haunted house attraction. But I suspect the title I'll be returning to most often in this collection is Love Story.

Despite the generic title, the film offers a unique, intoxicating brew. It sounds so simple; in New York on an arts grant, Habicht falls for a stunning Ukranian who he sees walking the city streets, carrying a slice of cake. Love Story sees the director taking his love of mixing truth and fiction into new territory, while enlisting passersby as co-conspirators.

Making Love Story, he found the process worked best when he embraced a "child-like intuitive zone", while finding strangers to interview in New York. His love of people and storytelling has never been more contagious. NZ Herald critic Peter Calder probably nailed it best, when describing the reaction at Love Story's debut screening: viewers were laughing — but "also gasping in amazement at the risky, strange, surprising and wildly romantic ideas sprinkled through it".

Ian Pryor is editor of NZ On Screen.