The Cow Collection

Lucy the Cow

New Zealanders have a nostalgic view of dairy cows. I call it the 'Lucy the cow' effect.

If you’ve ever watched Little House on the Prairie or any other tale depicting colonial farming, you’ll know the concept.

Lucy is the family cow. Every morning the kids wake her from a bed of hay in the barn, give her a scratch behind the ears, and hand-milk her on a stool. While that scene hasn’t existed for decades, the idea that cows live an idyllic life has endured — largely because the dairy industry has continued to depict it that way.

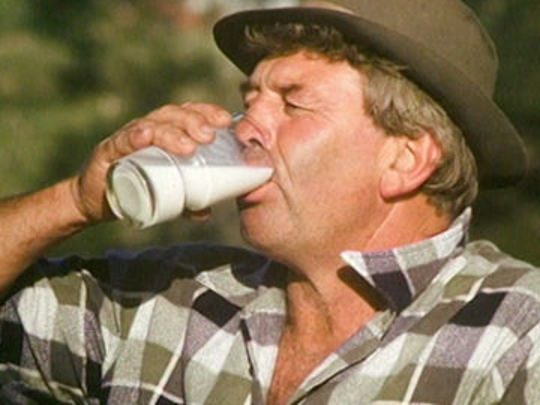

The opening scene of the NZ Milk Promotion Council advert.

Take for example this advert from 1981, produced by the NZ Milk Promotion Council. It opens with peaceful classical music and sun-dappled fields, as farmer Murray calmly calls his cows into milk. It’s all very peaceful, very loving, very simple. But is that actually representative of our dairy industry?

I spent several years researching New Zealand's dairy industry for a documentary series called Milk & Money. Through the process of interviewing hundreds of people, visiting farms across the country, and working on a dairy farm, I began to see the gap that exists between how the industry depicts itself and the reality.

New Zealand has nearly five million milking cows, producing a total of 21.7 billion litres of milk each year. The scale at which the country produces milk is literally tens of billions of litres beyond the simple agrarian lifestyle of Lucy the cow.

Our dairy cows aren't used to produce milk and cheese for a family and their community; they are factories in an intensive, multi-tiered manufacturing process that largely outputs milk powder for export around the world, to use in processed foods.

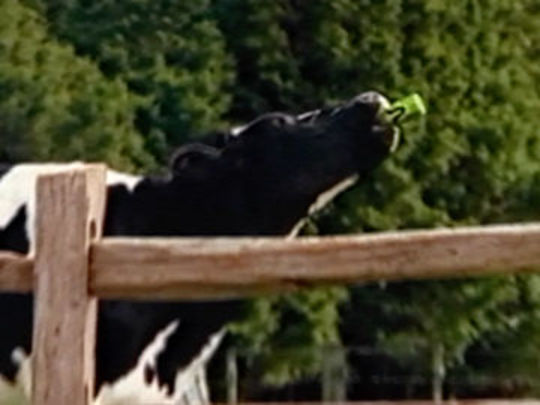

Of all of the clips in NZ on Screen’s Cow Collection, surprisingly the person who reflects on this best is the wonderful Suzy Cato. In a clip from her show Suzy’s World, she unpacks the process by which cows convert food into milk. Introducing us to Lucy the cow (I'm not making this up), she says, "[Meet] Lucy the black and white friesian factory…Yes, a factory, and the machinery inside this factory works very hard and very long hours to produce this … milk”.

An image from documentary series Milk & Money.

Suzy is spot on about how hard these cows work, and that's one of the biggest issues with the diary industry's ‘Lucy the cow’ framing: it makes it seem like the cows are happy and willing participants in this practice.

In reality, farmers push their cows' bodies to the limit in order to have them produce as much milk as possible. Cows spend most of their lives pregnant in order to continue producing milk, live roughly a third as long as their natural lifespans, and around a quarter have breast infections at any one time due to constant milking.

A cow’s poop actually provides a good visual indicator of how far their bodies are pushed. If you visit a dairy farm you’ll see the cows excreting literal streams of diarrhoea. If you’d never seen any different, you might think that is just how cow poop looks. Cows actually produce fairly firm pats under normal circumstances, but live with near constant diarrhoea due to the incredible strain their metabolism is placed under.

Cleaning up in the holding yard (from Milk & Money).

There are also millions of cows who are born from all those forced pregnancies, only to be killed. In 2020 the New Zealand dairy industry had 4.9 million calves and nearly two million were killed within days or weeks of being born — mainly boy calves that the industry has no use for.

A common theme from my research of the industry was how everything is focussed on maximising production. Another clip in the collection offers insight into this perspective. In an episode of Homegrown, comedian Te Radar interviews a researcher about their work on understanding cows’ emotional health. Te Radar asks why this topic is so important. The researcher responds, "Because contented cows are easier to work with, and we’ve shown in other situations they’re more productive".

Baz Macdonald tries to get a cow moving at 6am, during a week working on an organic dairy farm.

The dairy industry doesn’t give Lucy the cow a scratch behind the ear because it makes her feel good, but because it makes her produce more milk.

Ultimately, I understand why the industry depicts itself with the orange-tinted lens of a simpler time. It’s not even necessarily a lie. I’ve seen firsthand the loving relationship many farmers have with their dairy cows, including giving them names like Lucy. But it doesn’t come close to showing the full scale of our current industry, the true lives of its animals, or its environmental impacts.

- Journalist Baz Macdonald used to work at a freezing works for a holiday job. He writes here about making Milk & Money, and spending a week working on an organic dairy farm.