The Good Word - Series Two

Television (Full Length Episodes) – 2010

I got a bus to Taranaki and went into the village, and it was abandoned virtually. The houses were all empty and I think there was a couple of old old people living [there]. And one middle-aged woman invited me in for a cup of tea. When I explained that I had a sympathetic approach, she then showed me the mountan, the hillock where the cannon had been aimed at the people...

– Writer Dick Scott recalls visiting Parihaka while researching for his book about what happened

It's emotionally true. Factually there's there's quite a few alterations. Yes and I made stuff up, but I wanted to keep it emotionally accurate...

– Sue McCauley on her semi-autobiographical novel Other Halves, in episode three

He wrote out of time, of course. Nobody appreciated him in his time. But I read Sydney Bridge Upside Down again recently, and I was absolutely bowled over by it. Anybody in the English-speaking world would get a kick out of it, but it's essentially a New Zealand novel.

– Gordon McLauchlan on David Ballantyne's novel Sydney Bridge Upside Down, in episode four

I used to have a lot of imaginary characters around me when I was a child. So it came fairly naturally to me I think to write something like A Lion in the Meadow, in which the child's conviction confers reality upon the lion.

– Margaret Mahy on her timeless children’s story A Lion in the Meadow, in episode five

I think his writing ability came directly out of his yarning ability, and I think the yarning ability came from his time in the bush, when obviously those guys must have sat around of an evening, drinking whatever they drank or whatever, and spinning yarns.

– Colin Hogg on Barry Crump’s storytelling ability, in episode six

I thought to myself 'who I am iI writng this for? Ok I'll pitch it firstly at Māori, because they need to know . . . But I also thought, 'well it should also be pitched at Pākehā so they would know what happened, so they couldn't claim historical amnesia.'

– Ranginui Walker on his New Zealand history book Ka Whawhai Tonu Mātou: Struggle Without End, in episode seven

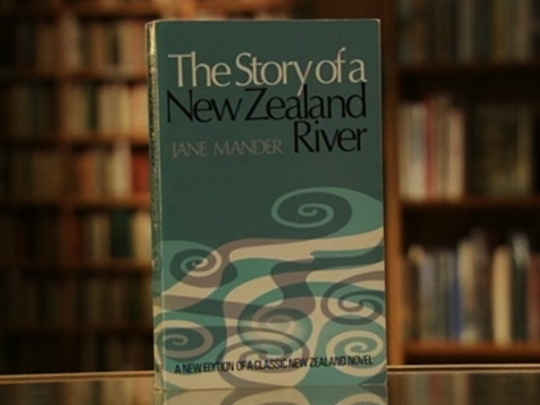

Jane Mander wanted to write, and of course in the time that she was writing, the only way you could be published was to be published in England. And so she wanted to be where the publishing houses were. She also wanted to have more experiences. She felt very stultified in New Zealand.

– Biographer Rae McGregor on Jane Mander writing her novel The Story of a New Zealand River, in episode eight

It is about people. And it's easy to write about people. Well you can get interesting songs, but an interesting person is easy to write about, and easy to read about.

– John Dix on Stranded in Paradise, his 1988 history of New Zealand rock’n’roll, in episode nine

You should try to avoid reading it as autobiography. Assume that there are elements that are there, but as soon as you read it literally as autobiography, you start making mistakes, because the novel shifts things around in time and place and character, according to the necessity of the book that's being written.

– CK Stead on Janet Frame’s semi-autobiographical debut novel Owls Do Cry, in episode 10

...there's been really vile books written about Elvis, like Albert Goldman's book on him, which if you like drinking poison it's a great read.

– Shayne Carter on books about Elvis Presley, in episode 11

I think there's a huge story in the settlement and creation of New Zealand as we know it, I suppose because I come from pioneer stock on both sides of my family. I feel deeply for New Zealand, I feel deeply for the men and women who made New Zealand what it is.

– Maurice Shadbolt on writing about New Zealand and New Zealand Identity, in episode 13

It was very hard for him to write about it, because he felt great disappointment. He felt betrayed by some people. At the same time, he didn't write the book to settle scores; he wrote the book as an account of what he thought, what he said and did, what other people said to him or did to him.

– David Lange's wife Margaret Pope on why he wanted an autobiography published, in episode 12

...Mum went to Holland and when I got back to New Zealand I was considered an overseas student, so i got speech lessons . . . I had this lovely old opera singer teaching me oratory. And so I immediately stood as a milk monitor and then a bus monitor, and then a prefect . . . when the protest movement started, there weren't that many people who could stand up in front of 2000 students and speak confidently and eloquently . . . it was an unusual skill at the time.

– Tim Shadbolt discusses the person history which fed into his book Bullshit and Jellybeans, in episode one