Children of Fire Mountain - Tom (First Episode)

Television (Full Length Episode) – 1979

Catching the Fire

Children of Fire Mountain was my first major kidult drama, an area in which South Pacific Television was gaining an international reputation. South Pacific's Head of Drama, John McRae, had amassed considerable experience in the format when he was with the BBC. I believe he not only understood the wide appeal these programmes had, but saw the opportunity to gain an international market and reputation.

Hunter’s Gold, the first, was a huge success. Gather Your Dreams followed a year later. Both were directed by Tom Parkinson, then I came on board to direct number three: Children of Fire Mountain. They were all written by Roger Simpson , and the last two were produced by a new arrival from Australia, Roger Le Mesurier.

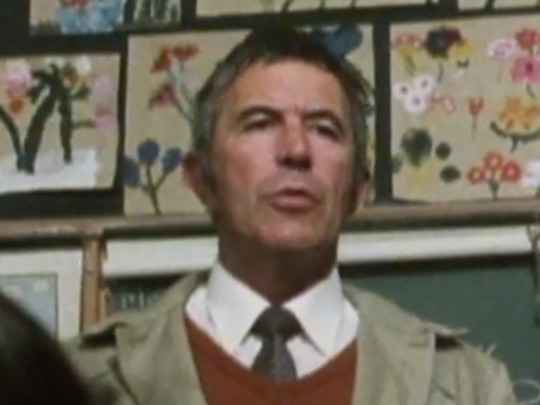

The story is aimed at children, but touches on some serious underlying themes: colonialism, racism, and the need for unity in times of disaster. It’s 1900. Sir Charles Pemberton (Terence Cooper) visits New Zealand, seeking a cure for his multiple aches and pains in the hot pools of Wainamu Spa. Finding relief, he conceives the idea of building an international spa on a piece of land with views across the lake to the Mount Wainamu volcano. But local businesses fear the competition, and the land is sacred to the local hapu. Not easily deterred, Sir Charles pushes ahead by fair means and foul, unaware that his major opposition comes from a gang of local children, Pākehā and Māori, including his aristocratic daughter Sarah Jane.

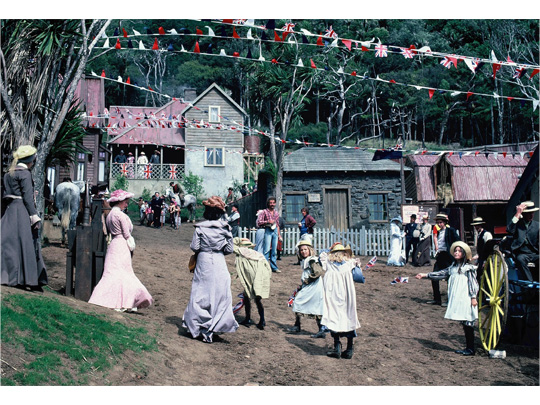

The main village set designed by Logan Brewer, built near Lake Wainamu at Bethells Beach/Te Henga.

As tempers rise in the town, so do the temperatures underground. The thermal area is heating up, leading to a massive explosion of Waimanu. The whole region is devastated by the eruption, and we end with old differences disappearing and a happier future looming. There is a light, comedic counterpoint to the tale of woe: the wickedness of bootlegger Doomy Dwyer, his wife Mabel and their hopeless assistant Sid, and their pursuit by well-intentioned policeman Sergeant Gillfillan (no kidult series is complete without a dose of chases and humour).

Children of Fire Mountain was shot almost entirely on location, with only three sets standing by as wet weather cover. The story was set in the town of Waimanu, which was purpose-built on the shores of Lake Wainamu, on Hap Wheeler's farm at Bethells Beach/Te Henga. I believe we were the first of many local and international productions to be based there, and the reasons were obvious. The beauty of the lake, untouched native bush, amazing iron sand dunes, and the wildness of Bethells Beach all made it an ideal location. But it made for a long shooting day. The car park was 50 minutes from Auckland. Another 10 minutes up the creek along the edge of the sand dunes got you to base camp at the Wheeler’s homestead; then finally, after wardrobe, makeup, and breakfast, a five-minute ferry across the lake to arrive at the set.

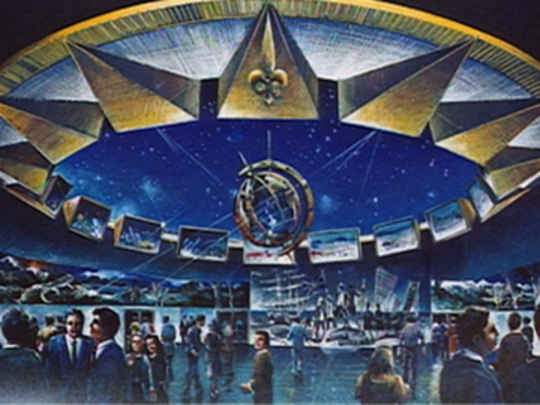

The mountain in the centre is a painting, mounted on glass.

Logan Brewer's town looked tremendous: settled in the hills with a commanding view across the lake, to the volcano rising above the black mass of the Wainamu dunes (thanks to now quaint pre-CGI glass shots). To get the view, the town had been built on a steep slope no town planner would have willingly contemplated. It exercised us all. Major complaints came from the kids when they had to run up or down it for more than one take, as well as the grips and electrics who had to carry tracks and lights. It also caused a few schedule changes: after heavy rain it was impossible to stand on the main street without slipping down it, and we had to move locations down to the muddy but horizontal lakeside. Some days after especially heavy rain, a rise in creek levels stopped us getting up the river to base camp.

Rotorua was the other major location. Thermal activity loomed large in the story. Not only were the streets of Waimanu packed with smoke machines, but almost every thermal area in Rotorua made an appearance: Hell's Gate, Wai-O-Tapu, the crater of Mount Tarawera, and especially Waimangu Valley, where the local iwi village was built. We filmed there for a couple of weeks, and every morning on the way in I passed a scientist processing readings from various pools. He was measuring thermal activity; he told me that before he died he expected the North Island to split along the band of activity from Whakaari/White Island to Mount Taranaki. Not yet thankfully, but there’s still time.

In preparation for Children of Fire Mountain, I had asked its director Tom Parkinson how he’d gone about auditioning the children for the lead roles in Hunter’s Gold and Gather Your Dreams. Approach schools that have an active drama group; explain the required age group; divide interested kids into groups of three or four; give them 10 minutes to come up with a short drama; pick the most promising performers and give them scenes to audition.

The first time, I spent hours devising plotlines to help them get through the incredibly short preparation time. Few wanted the help, and of those few, most quickly came back to enquire whether they had to do that plotline. They didn’t. The result was five wonderful performers: Paul Airey, Melissa-Aroha Baker, Ross Duzevich, Ian Narev, and Rachel Weston. They were the heart and soul of the story, and the whole production. It’s a total canard not to work with animals or children — the rewards are enormous. The freedom with which they give their time and talent, their laughter and love are not to be forgotten.

I believe it’s a moot point whether children act, or just have the confidence to be themselves. I like to think that I help them create a performance, although much of the work is done before they step in front of the camera. Jacqui Dunn, a great dialogue coach, made sure they knew and understood their lines, then let them be themselves. A good illustration of this is post-synching. The curse of filming during summer in the New Zealand bush is cicadas. Huge sections of location dialogue got buried under the noise, and had to be post-synched [rerecorded later]. In 1979 the system was clunky and lengthy. A scene was spliced in a loop or series of loops, with a chinagraph arrow running to the first word of dialogue. The loop ran until the actor refound the character and rhythm of the line, which could take time.

I remember John A Givins, who played Christopher Bain, initially found it very difficult. He didn’t believe he could speak as fast as the character he'd created, and was convinced we’d sped up the film. Eventually the character came back, and the process eased. For the kids, it was never a problem. Because their characters are them, the task was as natural as breathing. Most of the time it only took one listen and one take for an in-synch performance, in character to re-appear.

The Children of Fire Mountain crew. Peter Sharp is half-hidden near the top, behind someone with long blonde hair.

Compared with current filming schedules, we had a luxurious amount of time to shoot the series, almost six months. The stories from that time are legion. Leaving aside the night an overheated generator almost burnt down the whole of the Waitakeres, I’ll limit myself to two.

Ian Narev was a great natural comic. Neither Jacqui or I could stop him ad-libbing, nor, sadly, get him to save the best ad-libs until the camera was rolling. He was a singular boy; at one stage he converted Ross to Judaism, pork and shellfish disappeared form his menu. Then at Easter in Rotorua, Roger Le Mesurier and I gave Ross permission to go on a hunting expedition with his uncle, a moment seared in my memory mainly for the rage expressed by production manager Brian Walden, aka 'The Sarge', after learning we’d sent one of the lead actors off into the mountains with a gun. "He’ll be fine," was our reply.

Ross left on the Saturday, and was due back by Monday evening for a special dinner for the kids and heads of department. He was late and dinner was underway. The Sarge sat with a permanently raised eyebrow, and Roger and I intently studied our soup. Of a sudden there was a roaring of engine, a tooting of horn, a squeal of brakes. We rocketed outside and there standing astride a kunekune on the deck of a ute, gun in hand, was Ross, the picture of triumph. A rowdy, happy reception for the return of the wanderer, but in a moment of quiet Ian had something to say, "What do you think you’re going to do with that?" There was a dramatic pause. Ross looked down at the pig, then up to Ian, "Eat it." And the next weekend, with the exception of Ian, we did.

The thermal bath at the Waimanu Spa was built into the location set. Visually a warm, welcoming atmosphere was required: swirling mists rising from the steaming, healing waters. With the lake close by, filling the pool was not a problem; the temperature of the water was. Getting our star Terry Cooper into a cold bath at first call on a weekday morning was never a possibility. The water had to be heated. To save money, it was decided not to leave the heater on overnight but to get a junior member of the art department to turn it on at 4am: future Oscar-winner Grant Major.

Alone he faced the early morning drive out to Bethells, only to find it shrouded in fog. Undaunted, he set out to row across to the village, avoiding the motorboat at that hour in deference to the Wheeler's farm. At this stage, in the darkness and eerie stillness, doubts grew in Grant’s mind. Was he alone on the lake? He rowed on with a mounting sense of unease. Eventually he looked around to see a waka taua loom out of the mist. The full-sized canoe had come loose from its moorings, seen in the story as a phantom vision presaging the disaster to come. Grant swiftly reviewed whether a career in film was worthwhile. We’re all pleased that he decided to stay on board, rescue the waka, and turn the hot water on. It turns out that it would have been better to have left the water on all night; it was midday before the water was hot enough to put anyone in it.

Can I leave Fire Mountain without mentioning one of the great outtakes of all time? Late in the story, Sergeant Gillfillan (Waric Slyfield) moves to arrest Doomy, Mabel, and Sid, only to find them gone. Three times Gillfillan and his deputies rocketed out of the butcher shop, leapt on their horses and set off in pursuit. Three times the sergeant’s horse either farted or defecated when he hit the saddle. It was a long tracking shot, with complicated choreography to get the cast out of the shop and mounted, so we weren’t giving up easily. On take four everything was perfect: the cast safely off the shop verandah, the horses untied, Gillfillan on his horse, the horse a picture of discretion. Everyone was about to gallop away when a young girl, an extra with her mother, says "isn’t the horse going to poo anymore?" It would have been easy enough to get rid of the line afterwards, but sadly the whole cast and crew where shaking with laughter. Take five was the one.

-Peter Sharp's directing credits include classic kidult shows The Fire-Raiser, The Champion and Strangers, plus Mortimer's Patch and miniseries Erebus: The Aftermath.