Topless Women Talk about Their Lives

Film (Trailer and Excerpts) – 1997

A Perspective

At the time it emerged, Topless Women Talk About Their Lives was described as, "the freshest, cheekiest, most engaging film from New Zealand in years." (Paul Byrnes, Sydney Film Festival, 1997). That's a fair summary. The decade previously had only fitfully been disturbed by anything special, and certainly not much by anything that was funny.

Harry Sinclair kicks off his pleasingly tangled narrative with an irreverent poke at one of New Zealand cinema's sacred cows. While visiting the beach where The Piano was filmed, would-be screenwriter Ant (Ian Hughes) hurls his latest failed script away in despair. A visiting German producer finds the discarded pages, takes them home and makes the movie.

It's hard to escape the notion that Sinclair is making a personal comment on the vagaries of fate, and of course, he is.

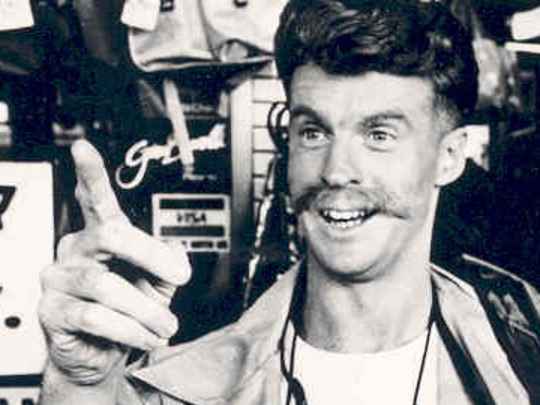

As a member of the iconic song and comedy duo, The Front Lawn, Sinclair had begun extending his love of acting and writing into the medium of film. But he was experiencing problems getting anyone to take him seriously as a director. So he bought a video camera and started making little films without any funding.

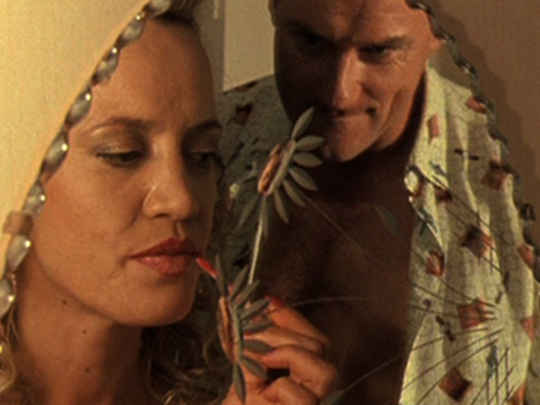

Working with actor friends, and workshopping ideas as they filmed, Sinclair discovered a different way of developing stories. Somewhat in the manner of English director Mike Leigh, he found he could create complex scenarios while actually making the film. Lead actress Danielle Cormack's real-life pregnancy even became a key part of the story.

This improvised style was complete anathema to traditional funding bodies like the New Zealand Film Commission, but Sinclair was both clever and lucky. Having initially decided he had no chance of getting backing for a film, he successfully pitched the idea of making a mini comic soap opera to TV3. The episodes would be three or four minutes long, designed to fit between other programmes late in the evening. Only the first few would be scripted. The rest they'd make up as they went along.

A good plan. But after about a dozen episodes had been shot, Sinclair realized he had the equivalent of half a feature film in the can. He offered up the whole kit and kaboodle to the Film Commission as a cheap ‘work in progress' and invited them to help pay to finish it.

Given the quality of the work done so far, it was an irresistible proposition, and the Commission would have been mad to turn it down. They didn't.

The Gen X acting talent, particularly Cormack (radiant as Liz) revel in the freedom that Sinclair gives them to explore the irreverent zest of being young: there's weirdness and normality, jealousy and friendship, depression and exhilaration, falling in and out of love, and an eponymous film within a film.

Mid-way through the film Topless Women takes a perverse left turn into more downbeat territory. Characters who start out loveably quirky become miserablists as fate deals them losing hands, and the comic energy of the movie's first half dissipates, before recovering its joie de vivre late on.

The goodwill generated by the opening was not entirely spent. Various bands from the Flying Nun stable including indie legends The Clean, Straitjacket Fits, The Bats, The Chills, and Chris Knox, ensure the soundtrack jangles proceedings along; surreal, off-kilter moments (a swimming rabbit, a coathanger noose) and realism (a gritty birth scene featuring Cormack's two-week old baby made up in slimy post-birth fx) punctuate the melodrama; and the casual energy of youth is captured in naturalistic and engaging performances.

Some critics decided that the lives talked about in Topless Women left them with more of the dull ache of irony than a sense of profundity, but most critics reacted favourably. Pavement's Bernard D. McDonald's caught the general mood:

"It's both welcome and refreshing to have a great comedy we can laugh ourselves silly with. Topless Women is inspired mayhem, a film so loose in its production yet so tight in its construction that everything is virtually faultless ... Topless Women is the first lighthearted film which embraces our New Zealandness ... This is the most refreshing, light-hearted and unpretentious feature film New Zealand has ever produced."

Topless Women cleaned up at the 1997 NZ Film & TV Awards: Best Film, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Actor (Joel Tobeck), Best Actress (Danielle Cormack), Best Editing (Cushla Dillon), Best Supporting Actor (Andrew Robertt) and Best Supporting Actress (Willa O'Neill).

Its box office score was also respectable for a small arthouse film and it sold internationally. Topless Women competed for the Golden Leopard at Locarno, screened at Montreal, and won an audience award at Portugal's Fantaspoto festival.

The production of the film was a model of low-budget DIY creativity and the results were a shot in the arm for the way feature length stories could be successfully constructed in New Zealand. As Cormack summed it up:

"There was a director and three other actors that didn't have anything to do. So we did it [initiated Topless Women] to do something and we did it for free. Look what it evolved into! Anyone who sits back and just complains about no work, no money, no finance, to me is just lazy."