Stalin's Sickle

Short Film (Full Length) – 1986

A Personal Perspective

I discovered the original short story 'Stalin's Sickle' in the pages of The Listener in 1981. I was at Ilam art school studying film. I was immediately attracted by the blend of realism and whimsy in Michael Morrissey's writing. So I cut the story out of the magazine, and filed it away as a possibility for the future.

The next few years were tough. I made a couple of short films, and nursed hopes for bigger things, fanned by the breakout success of local movies like Goodbye Pork Pie and Smash Palace. But the feature film boom which suddenly got underway in the wake of those pictures had a downside for emerging wannabe film makers.

The NZ Film Commission, which had initially been receptive to assisting filmmaking of all kinds, abruptly lost interest in short films. Features were it, and nobody was going to let a beginner loose on a feature. This went on for a few years until inevitably the question began to be asked — where are new feature directors going to come from? So a good deal of pressure built up on the Film Commission to do something for new talent. One of the results was the Commission founding the Short Film Fund late in 1985.

At this time, the definition of a short film was a good deal wider than today. For a blessed window of time, up until the inception of the so-called 'Bonsai Epic' scheme round 1990, a short film could be anything up to an hour long, and could be aimed at television as well as theatres. I wasn't aware of any such historical perspectives at the time. I was just very eager to turn a short story I loved into a movie. The new fund gave me an opportunity to make Stalin's Sickle, and I grabbed it with both hands.

Directing Stalin's Sickle was probably one of my happiest and most satisfying filmmaking experiences. There seemed to be a charmed pathway from vision to execution, with all the many collaborators involved giving it their best shot.

For me, the stylistic key which unlocked a way to adapt the material was the work of Dennis Potter, particularly Pennies From Heaven. The TV series used theatrical techniques to stage seamless transitions between objective and subjective points of view.

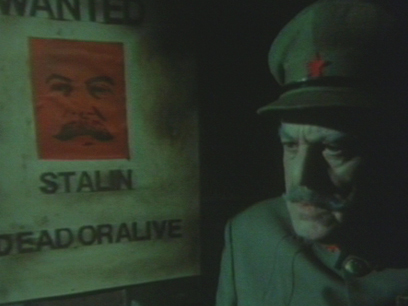

There were two main problems that needed to be solved in order to make a viable film. The first was to educate a modern audience about who Stalin was, and the second was to create a vivid depiction of the story's world — 'Red' baiting, fiercely Catholic, working class New Zealand in the early 1960s.

To assist with both these issues, I recruited Anne Kennedy to write the script with me. Working with feedback from Caterina De Nave, Anne pumped a good deal of her own Catholic childhood into a long pass at the screenplay. I subsequently had to cut that draft back, but tried hard to retain the essential feel of Anne's writing.

Casting genius, Di Rowan — who has discovered an incredible string of brilliant child actors over the years — pulled off another of her many conjuring tricks, locating Stacey Adams to play the lead role. I'd had some sleepless nights up till then, imagining my future in the hands of an eight-year-old; but little Stacey was brilliant.

I'd met Di's partner George Lyle when he was swinging a boom on the set of Worzel Gummidge Down Under. By some unknown act of intuition, I divined that George might make a great First Assistant Director. I don't know whether he was already contemplating a career change from booming to scheduling, but he turned out to be a marvellous 'first', not to mention ersatz production manager. George and Second Assistant Maria Saunders really helped pull the production together for a director who was still green in terms of professional organisation.

I'd already worked with cinematographer Murray Milne on two previous films, so we were a pretty tight unit by this time. I enjoyed devising some of the more complex tracking shots with him, and Murray's lighting was fantastic.

The film was edited the old-fashioned way on a flatbed Steenbeck, which was temporarily housed in a hallway at Wellington's Production Village. I got terribly stuck while cutting the end sequence. I'd covered a key bit of action with a long tracking shot. There were only two takes. The beginning of one was good, but the end was crap. While the end of take two was great, the beginning wasn't as good as I remembered (on-set wishful thinking can create powerful mirages for inexperienced helmers —particularly when working without monitors, as we did in those far-off days).

I stewed on my dilemma noisily enough to attract the attention of a passing flash commercials director, who asked me what the problem was. I huffily told him (what did he know anyway, he only directed commercials). He looked at the shots, and pointed out there were two black frames in the middle where an actor crossed directly in front of the lens. "You can swap takes on the black frames", he said, and trotted off to a long champagne brunch with his flash clients.

So I learned two things that day. One, that movies really are magic. You just have to know the right tricks. And two, you can never eat enough humble pie in this business. Thanks, Waka.

- Costa Botes has directed dramas (Saving Grace), documentaries (When the Cows Come Home) and films that are difficult to classify (Forgotten Silver).